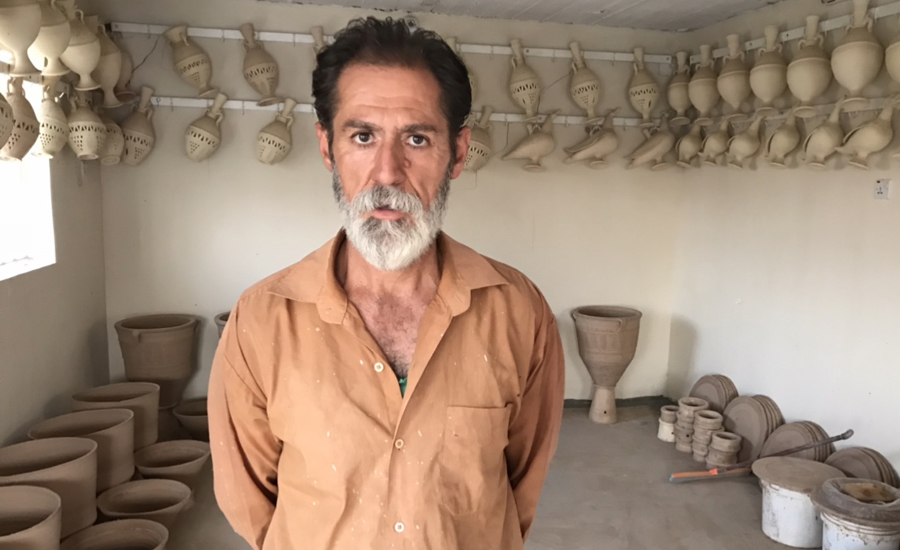

COVID-19 has forced a skilled and experienced Kaka’i potter to shut down his business. In addition to the human cost, the coronavirus pandemic has caused a significant number of small businesses in Iraq to close, resulting in the loss of hundreds of jobs.

“May God help me take care of my children; the Coronavirus cost me my job. I will have to work as a construction worker at this age,” said Safin Jamal, a 65-year-old potter.

Safin wept as he closed the door of his factory for the first time in its 100 years of existence. He is one of the victims of the economic collapse brought by COVID-19; forced to leave behind not only his job, but a trade he inherited from his ancestors.

Safin is the son of the well-known artisan, Jamal Zain al-Abadin Kaka’i, known as “potter Jamal”. They belong to a prominent Kaka’i family that resides in Daquq district, south of Kirkuk province. Jamal opened the pottery factory a century ago but Safin reluctantly closed his business in early June.

we lost all the customers; our customers were mostly from central and southern Iraq

“The curfew forced me to close my factory for a month. My children and I resumed work in late May, but we lost all the customers,” he said, “our customers were mostly from central and southern Iraq.”

The Iraqi government imposed a nationwide lockdown in March to contain the spread of COVID-19.

.

Safin’s factory is located on the Baghdad-Kirkuk road. Many of his customers would purchase his wares as they travelled between the northern, southern, and central Iraqi cities.

Safin, whose family has passed the profession down from one generation to the next over a century, is one of the few craftsmen left in the country. Now Safin fears that his family might permanently give up its trade because of the lockdown.

Safin has a family of six, and they all worked at the factory. His father died in 2018 while working in the factory.

We consider the profession holy and important because one of our grandfather’s dying wishes was for us to keep doing this work

“This craft was my father’s, grandfather’s, and my ancestors’ livelihood. We consider the profession holy and important because one of our grandfather’s dying wishes was for us to keep doing this work, and that this factory should never be closed down.”

Last week, the first coronavirus case was recorded in Daquq. In response, security forces have taken stricter measures, including closing local shops, banning travel outside of the district, and limiting traffic inside its borders.

“We were the first to be affected by the measures, and to such an extent that I had to close my factory because I was just sitting around, staring at my pottery,” Safin said, describing how sales of pottery immediately dissipated with the announcement of travel restrictions.

.

The day he shut down his business, Safin started working as a day labourer to make ends meet. Being a labourer is quite challenging for him due to his old age, but he said he is still grateful to find work.

I cried a lot and begged God to have mercy on me and my children on the day I closed my factory

“I cried a lot and begged God to have mercy on me and my children on the day I closed my factory.”

The history of the Kaka’i minority in Daquq can be traced back to antiquity, with its people spread out among 15 villages and cities in the district. The community has suffered greatly during the pandemic as insurgent attacks increased throughout the district and professionals like Safin are forced out of business.

Safin explained that he had participated in pottery exhibitions both inside and outside Iraq.

“The last time my father and I participated in a pottery exhibition was in 2013 in Turkey, where we won the first place.”

Safin and his father had sculpted an 18-meter-long clay model of an airplane a few years ago and placed it in front of the factory, attracting many passers-by and drawing more customers into the factory, Safin said.

Hussein Darwish, a close friend of Safin’s father, explained that Jamal did not regard the pottery craft as an ordinary one, but had passion and fascination for it, and that Jamal worked as a sculptor and “constantly talked about how he wished to contribute [to art and culture] through his work.”

The major problem families like Safin’s face is that the government has imposed a lockdown without providing financial relief to business owners. Therefore, they must shoulder two burdens: make a living and protect themselves from infection.

The re-imposition of the lockdown came after a resurgence in coronavirus infections, reaching 17,770 recorded cases with 496 deaths throughout the country.

Safin has not removed his equipment from the factory and says that he follows the news with his children every day, wondering when the pandemic will pass so he can go back to work.

“The end of the coronavirus means restoring our source of income and obeying the will of my grandfather to sustain the profession.”