Daesh’s violent targeting of Iraq’s religious minorities between 2011-2015 destroyed communities and shattered infrastructure. Now, the lives and livelihoods of religious minorities are once more under threat as a result of Covid-19, the measures to contain the pandemic, and from Daesh, which is once more on the march, writes Ewelina Ochab, a human rights advocate working with the IDS-led CREID programme.

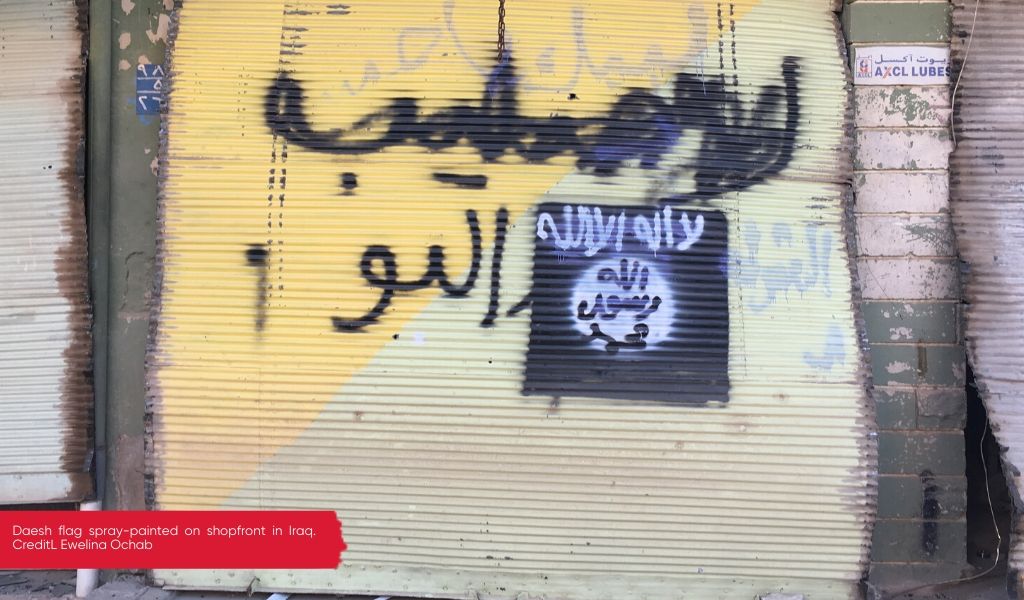

Daesh flag painted on shopfront in Iraq. Credit. Ewelina Ochab

Covid-19 is adding to the pressures already experienced by poor and vulnerable communities all over the world. While it has put life on hold for many, there are some who have been using the pandemic as an opportunity to further their goals. Recent reports suggest that Daesh (also known as the Islamic State or ISIL) has been using the pandemic and particularly the fact that state resources are re-directed to respond to it, to grow in power yet again.

Mass atrocities against religious minorities in Iraq and Syria

Only six years ago, Daesh unleashed mass atrocities in Syria and Iraq. These included killings, physical and mental abuse, rape and sexual slavery, enslavement, torture and inhuman, degrading treatment, forcible transfer of populations, and much more.

Daesh specifically targeted religious minorities like Christians, Yazidis, Kakai’s and other groups because of their religion. Described as “infidels” by Daesh propaganda, as propagated in its recruitment magazine Dabiq, they considered members of religious minorities as legitimate targets to be destroyed, or conquered and enslaved.

The Council of Europe, the European Parliament, several governments and parliaments have recognised the atrocities of Daesh to amount to the legal definition of genocide under the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

The atrocities have resulted in religious minority groups in the region facing possible annihilation.

For example, as a result of Daesh’s genocidal campaign, between 2011 and 2015, the Christian population of Syria has halved from over 2 million to less than 1 million, and in Iraq, the Christian population dropped from 1.4 million in 2003 to 260,000 in 2015. Yazidi communities in Iraq have faced a similar fate.

During some of the most violent attacks in 2014 when Daesh was trying to establish the self-proclaimed caliphate, thousands of people were killed. The exact numbers are not known. Women and girls were abducted, forcibly converted and forcibly married to Daesh fighters, and abused by them. Boys were abducted to become soldiers and forced to kill in the name of Daesh. Churches and places of worship were plundered and religious symbols destroyed.

Shooting range outside Qaraqosh cathedral in Iraq. Credit. Ewelina Ochab

This is the destruction I found during my trip to the Nineveh Plains villages in Iraq, in early November 2016, a few weeks after the area was liberated from Daesh.

However, there is also a part of the destruction that the eye will not see. This is the psychological impact on the targeted communities that will haunt the victims, survivors and whole communities for generations.

Six years later, thousands of women and girls are still missing. Six years later, new mass graves continue to be discovered in the region shedding light on the fate of some of those abducted and missing. Six years later, the region is still a long way from what it was before Daesh.

In December 2017, the Iraqi authorities announced that the fights against Daesh were won. However, such an announcement has been premature. Although Daesh may have lost most of their territories they once referred to as ‘caliphate’, they have continued to be present in the region. Furthermore, Daesh is more than just a group of fighters. It is also an extremist ideology that continues to flourish as there have been no adequate counter measures and campaigns to contain its spread.

Communities and infrastructure in the region still very vulnerable

Since the liberation of the regions once held by Daesh, religious minorities continue to struggle to return to their homes.

Thousands of people forcibly displaced in 2014 still live in IDP camps in Kurdistan or refugee camps elsewhere. The region is not fully rebuilt yet and reconstruction will take significant time and financial resources. Some areas, such as parts of Sinjar, are uninhabitable because of the mines still lying in the ground. Many believe that they can never be safe again in the region.

And now they are facing the threat of Covid-19. Living in IDP- and refugee camps makes them extremely vulnerable to contracting Covid-19 since social distancing and other preventive measures are difficult to implement. Furthermore, they have limited access to medical assistance and medications.

Those who have returned to their homes once taken by Daesh are not necessarily in a better situation. As well as an urgent need for reconstruction, the infrastructure in the region is not fully functioning either. In Sinjar, the health system is on its knees. With the security forces turning their attention to implementing lockdown measures, Daesh and others are re-emerging to attack minorities they previously had targeted, such as the Kakai’s. The Iraqi President himself recommended that this minority either evacuate their villages, form their own security force or hire special guards, which does not bode well for stability in the region.

Already in May this year, Daesh began increasing its attacks amid political instability following the government crisis, divisions among political parties, and security weakness that followed the withdrawal of the US-led coalition amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

Daesh’s growing power could be the final straw for the religious minorities in Iraq and the region, whose survival is already hanging on a thread. While efforts to address the Covid-19 pandemic are vital, they should not be at the expense of neglecting the very real threat posed by Daesh. As we know all too well from six years ago, this threat cannot be underestimated.

This blog is part of the Religious Inequalities and the Impact of Covid-19 series, commissioned by the Coalition for Religious Equality and Inclusive Development (CREID). Ewelina Ochab a legal researcher and human rights advocate. She works on the topic of the persecution of minorities around the world and is co-founder of the Coalition for Genocide Response. Follow Ewelina on Twitter.