Religious discrimination can be a driver of poverty overall and harm many who those who are most marginalised and left furthest behind. A new CREID paper by Professor Katherine Marshall, finds that how we are able to identify and measure religious discrimination matters a great deal on understanding the scale and depth of religious inequalities.

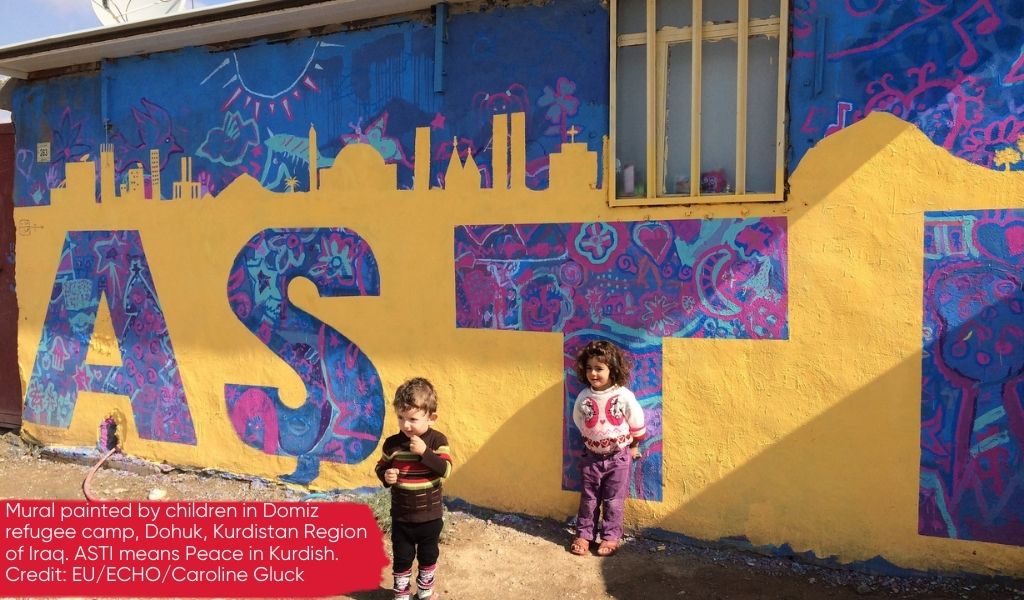

Mural painted by children in Domiz refugee camp, Dohuk, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Asti means peace in Kurdish and the mural was designed to promote a message that Christians, Yazidis and Muslims can live peacefully together. Credit: EU/ECHO/Caroline Gluck (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Religious discrimination and persisting inequalities matter because of their human cost and, more broadly, implications for peace, stability, and plural, inclusive societies.

A new Working Paper, published by the IDS-led Coalition for Religious Equality and Inclusive Development (CREID), reviews the complex landscape of approaches to assessing and measuring both the status of Freedom of Religion or Belief (FoRB) and the degree to which this human right is being violated or protected.

Entitled Towards Enriching Understandings of Freedom of Religion or Belief: Politics, Debates, Methodologies, and Practices, the paper provides insights on the strengths and weaknesses of specific approaches to assessment, along different criteria such as who is collecting the data, what sources are used, which groups are covered, how representative are they, the frequency of data collection and the approaches to their interpretation and classification.

The complex picture that emerges from this review leaves fundamental questions as to why worsening trends around FoRB violations are emerging so consistently.

8 recommendations for improving how to assess and respond to religious inequalities

The paper finds that measures for understanding, assessing and responding to religious inequalities are strikingly missing in methodologies and indices that assess human development progress, including the 17 SDGs and 167 targets and human rights reviews.

Here are eight considerations for improving we assess and measure FoRB, and the violation of this human right:

- Definitions as a starting point: How religion is defined presents specific and significant issues. For example, the vulnerability of religious communities is often linked to non-religious as well as more strictly religious motives, with behavioural, practise aspects of religious communities playing roles. Any mechanism aiming to effectively address persecution has to begin with its definition and understandings of early warning signs, as well as positive appreciations of effective responses – and in all three instances, there are significant weaknesses.

- Currently, there is no widely accepted methodology for different tier analysis on FoRB across local, national and the global. For example, while country-specific thematic analyses do exist, they offer little framework for comparison among countries, and often focus on a quite narrow range of issues and eschew judgements either on the overall situation or on trends. Robust case studies and country overviews are needed to gain a granular understanding of the particular conditions that account for the trends seen in data and circumstances at a country level.

- Rankings or ratings are helpful for broad brush appreciations but are fraught with some significant pitfalls. They offer limited insight into the causes of differences between countries, differences which cannot readily be standardised, given the vital importance of context in assessing how FoRB is understood and applied.

- The data used in virtually all the methodologies and reports are imperfect and efforts to address flawed data bring some specific risks and potential distortions. One significant data challenge is around the sensitivities in assessing violations and the sometimes necessary secrecy or discretion needed around data collection and verification, as well the wide diversity of contexts themselves. For example, over-reporting in freer-access countries can lead to saturation, while under-reporting in countries with more repressive governments can lead to major information gaps and distorted data. While self-reported data or data obtained through interviews may be limited by distrust or confidentiality concerns.

- Tradition-focused assessments (e.g. looking at anti-Semitism, the persecution of Christians or Islamophobia) provide greater levels of detail and context, including transnational trends and comparisons. The indicators needed for these assessments, however, do not always allow for a wider analysis of the broader policy and social context. Additionally, there’s also continued need to ensure that the ‘World Religions’ do not overshadow very serious impacts on much smaller communities, such as the Kaka’i community in Iraq.

- Ultimately, subjectivity is hard to avoid. Even where methodologies are broadly seen as objective, for example by doing their data-verification through double-blind coding, and using inter-rater reliability assessments and carefully monitored protocols, they are inseparable from the primary sources that go into the analysis, all of which are subject to at least some element of selectivity and judgement. As well as having access to data, it’s still essential to acknowledge existing power structures and understand that adding resources into a context where different actors have different power, social status, social and political capital, etc. is far from neutral, risking, for example, maintaining or deepening inequalities.

- There are complex practical and ethical questions around incident reports and ways to link them to policy instruments. For example, in relation to hate speech and violent incidents, there are particular challenges in relation to primary data sources such as the position and identity of the data gatherer, or variations in the data-gathering processes. Issues of trust and trustworthiness are involved which pose significant ethical questions about both treatment of data and how far the data can be generalised and accepted as representative and trustworthy. At the same time, the voices that courageously report, despite risks, deserve to be heard.

- Cross-national comparisons tend to centre on the nation-state, with macro-level indicators and high levels of generality across what may be very different regions and communities. Measuring and assessing non-state actors and social attitudes more broadly is equally critical, but especially difficult. These include groups far beyond religious institutions, such as organised crime and indigenous authorities.