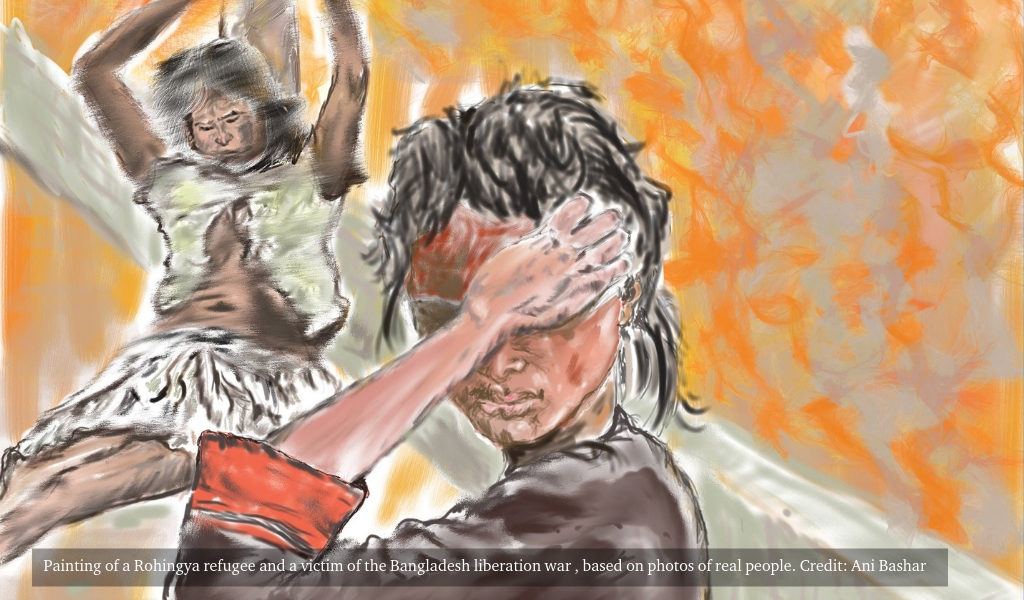

On World Refugee Day, CSW’s recent report on ethno-nationalism, religious intolerance, crimes against humanity and genocide in Myanmar (Burma) is a stark reminder that, while the media spotlight and international condemnation seem to have faded away, violence and persecution are real and a daily occurrence in the lives of all ethnic and religious minorities.

The figures in the painting are based on photographic images of two real people. In the foreground, is a Rohingya refugee in a camp in Bangladesh and in the background figure is based on a photo of a victim of torture and sexual violence from the 1971 war of liberation in Bangladesh. Credit: Anil Bashar (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The small and stuffy committee room at the top of the UK’s labyrinthian and archaic parliament, where the report was launched on 21 May under the auspices of the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for Burma seemed far removed from the corridors of power, perhaps mirroring the feelings that many of us felt as speakers shared their frank and uncensored accounts of the experiences of Christians and Muslims: what (more) can we do?

Does unpicking the complex situation in Myanmar provide possible courses of action for both local civil society and the international community?

Views at the launch of this report varied on which aspect of the many headed hydra that is the conflict situation in Myanmar should command our attention.

The answer is it is all inter-connected and part of the same picture, hence CSW’s report and its title, “Burma’s Identity Crisis”. There is the issue of the Burmese Buddhist nationalist ideology, which is comprehensively covered in the report: Kai Htang from the Kachin National Organisation (whose quote I borrowed for the title of this blog) took us back to the colonial era – the Burmese already had a superiority complex back then, citing an ancient saying “We Burmese are the Masters”. A new and more toxic variant of this is being rolled out across schools, through propaganda and public pronouncements by Buddhist leaders such as “it’s ok for Buddhists to kill non-Buddhists”.

Kyaw Win from the Burma Human Rights Network pointed to the might of the rampant military intent on preserving economic assets and political power. The crushing of Myanmar’s minorities was a deliberate political project supported by legislative measures such as the denial of citizenship as well as the brute force. Stateless refugees become stranded (and criminalised) in their host countries.

Tun Khin from the Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK shared the inescapable extent to which the genocide against Rohingya Muslims has been perpetrated. Over 600,000 Rohingya refugees have fled targeted violence and human rights abuses in Burma/Myanmar since August 2017. The substantial human rights abuses are sadly well documented –both in this report, and more famously in the UN report which first declared genocide.

It seems after that initial declaration of genocide, little has happened, and many in the room deep frustration at apparent inertia from both the British Government and the international community more broadly, which seems to accepted the declaration as a fait accompli. After Bosnia Herzegovina or Rwanda, have we become utterly powerless to intervene in the face of such blatant horror?

Our attention kept coming back to two cornerstones of the ongoing conflict:

- Perpetrators (or facilitators) of violence

- Perpetrators of hate

Targeting the perpetrators (and facilitators) of violence

On the former, there’s no doubt that they need to be brought to justice, and, in the meantime (since all acknowledged what a lengthy process this would be) targeted sanctions should be applied. But this would be enough to take the wind out of Myanmar’s armed forces, the Tatmadaw’s sails? The sanctions would also require significant international coordination to be effective. Can some of the larger players, such as China and Russia, in the region be persuaded to take part? If, as Kyaw Win proposed, the underlying driver for the military brutality is protection of power and assets, might sanctions make them re-double their efforts?

Paul Scully MP, who was co-chairing the meeting, expressed support for a more non-interventionist approach, focused on growth (perhaps unsurprising given his role as the Prime Minister’s Trade Envoy for Burma): if we help the people of Burma/Myanmar out of poverty, they will be more empowered to resolve the conflict themselves (which is, in fact, a multiplicity of conflicts, with some, like the Karen, dating back to independence in 1948).

But conflict and development will not happily coexist – aid supplies to Rakhine have been blocked and there are significant curbs on what both international and national NGOs can do. But, if aid and investment continues to pour into Myanmar, is there any opportunity to leverage influence here? It will be interesting to see what the response to the UN’s recent threat to withdraw aid might be.

Targeting the perpetrators of hate

Perhaps a new(er) aspect of the conflict in Myanmar is the rapid and systematic spread of hate and intolerance, both online and offline. Although there’s only 33% Facebook penetration in Myanmar, this still represents 18 million users.

Credit: thoughtcatalog.com

At the height of the Rohingya crisis, reports started to emerge, detailing the role Facebook has inadvertently played in rapidly fanning and spreading hate speech, particularly against Rohingya Muslims, and while it banned a number individuals associated with Myanmar’s armed forces , including , Facebook is fighting a losing battle. And there’s nothing to stop the hate from spreading to other platforms. In fact, the CSW report starkly points how hate speech is spread through newspapers, magazines and television as well as materially through billboards – there’s a shocking spread in the report with photos of examples of these.

With the elections due next year, the risk is that hate speech will only increase.

Rushanara Ali MP, who also co-chaired the event, felt that curbing hate speech is an area where the Government might be able to make more progress and pledged to take this matter further with parliament.One option could be greater support for “counter” campaigns, such as the Panzagar (“Flower Speech”) campaign?

Beyond helpless to on the ground action

Benedict Rogers, CSW’s East Asia Team Leader, who authored the report also pointed to another option: “building bridges” between communities and faith. This is an area we’ll be actively exploring in the recently established Coalition for Religious Equality and Inclusive Development (CREID), of which CSW is a key partner. We’ll be looking at how to deliver interfaith services, working in the poorest communities where sectarian tensions are high. We’ll be targeting young people from across different faiths, building their capacities to serve their communities.