Heritage sites play a vital role in sustaining community identities as well as individuals’ personal wellbeing. In the Middle East, religious minorities have not only suffered physical violence at the hands of Daesh but also systematic destruction of the heritage sites which nurture their very identities, writes Sofya Shahab.

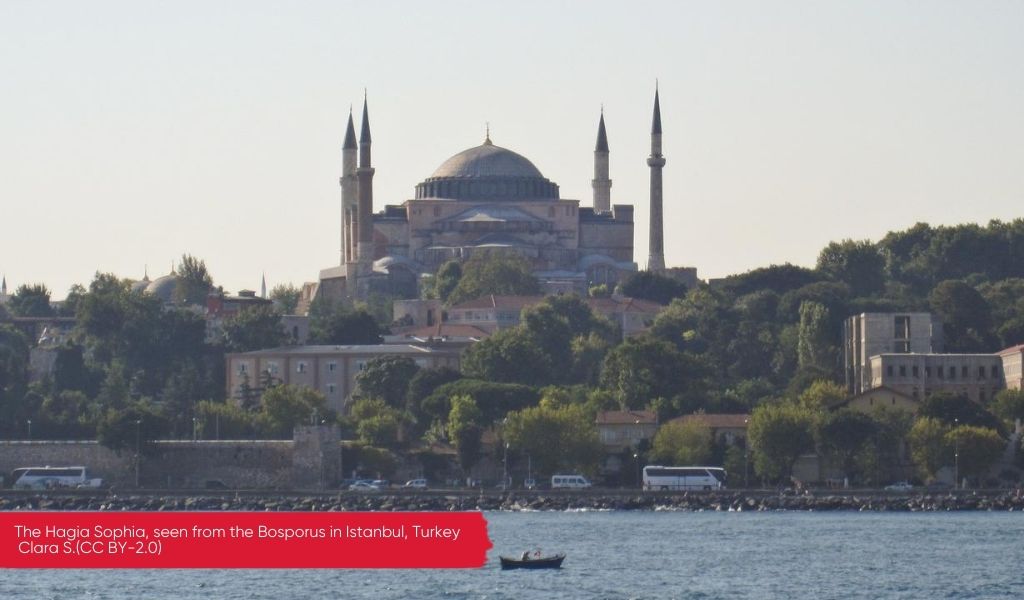

The Hagia Sophia seen from the Bosporus, Istanbul, Turkey. By Clara S. (CC BY 2.0)

For almost 1,500 years, the distinctive domes and minarets of the Hagia Sophia have floated above the western bank of the Bosporus. It is one of Turkey’s most iconic landmarks with significance for both Christians and Muslims, as well as those who celebrate the formation of Turkey as a secular state. The site is also on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

Turkey’s top administrative court, however, recently declared the conversion of the Hagia Sophia into a museum by Kemal Ataturk in 1934 as unlawful. This declaration has caused much controversy. Revoking the Hagia Sophia’s museum status risks altering the universal value of the building and many of those who have related to the site as part of their heritage may be excluded.

Who controls the past, controls the future

Political deployments of heritage have often raised questions regarding who owns the past and how it is used in the present. As George Orwell wrote in his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, ‘Who controls the past, […] controls the future: who controls the present controls the past’.

Throughout history, heritage has been employed as a tool in the unmaking and remaking of social practices and identities as a means of exerting and securing power. Religious sites are spaces of particular contestation due to the power they have in creating community and ways of being: to the extent that by altering religious sites it is possible to alter society.

In the case of Iraq and Syria, as well as carrying out mass atrocities against ethno-religious minority groups, Daesh also carefully and publicly targeted cultural heritage linked to various religious groups in their desire to create a homogenous neo-Salafi society. Daesh’s heritage destruction extended to Shi’a, Yezidi and Christian shrines, temples, mosques and churches. The extent, speed, and variety of their campaign against the diverse heritage of the region, with the aim of establishing their ‘caliphate’, shocked people around the world.

Daesh’s actions have caused millions of Iraqis, particularly religious minorities, to flee their homes, and flee their country.

Religious minorities in Iraq struggle to maintain their identities following Daesh violence and destruction

In my research among the Iraqi Assyrian community who had been displaced to Jordan, the desecration of their religious heritage by Daesh was experienced as a visceral form of violence, forcing them to leave their homes and country.

Destroyed church in Qaraqosh, Iraq. Credit. E. Ochab

Alongside the ancient Assyrian sites such as Nimrud and Nineveh, it was the loss of their local churches and religious icons which was felt most virulently. These forms of heritage provide tangible markers that cement belonging and enable religious practices and rituals. They not only provide the space where religious identity is performed but religious heritage can also contribute to that religious identity.

Among my interlocutors, the churches in Iraq functioned as a ‘home’, a sanctuary of peace where they could commune with one another, and communicate with God and those who had shared in their worship over the centuries. One of the young women I worked with explained how the church of St George in Bartella had been special to her. She recollected how,

“Whenever I was feeling sad, when I was feeling devastated or pressured, or I just wanted to go and cry, I would go to that place where I would feel it as a sacred haven to let my feelings out. It was a sanctuary […] No matter how bad or how sad I would feel, whenever I would enter the church I would feel relieved and calm. I would sense the positive energy and I would know Jesus Christ, I could feel him in the church.”

The physical space of the church created a spiritual connection to God that reaffirmed her faith. In this way, it is not just the people that make the church, but the material fabric of a building can also contain part of a community’s soul, as the material evokes the immaterial.

The rise of Daesh and subsequent re-configurations of heritage, has meant that minority communities such as the Assyrian Christians and Yezidis have lost vital places in which their religious identities can be formed and practiced.

Freedom of religion or belief is directly linked to heritage

These connections between heritage and religion have ongoing implications for the freedom of religious beliefs, especially among minority groups in the region.

This is because, when access to religious heritage is restricted or these spaces are destroyed it is not only communities’ physical presence that is being removed from the landscape, but also their identity as signified and maintained through their intangible cultural practices which occur within and are enabled by this heritage.

For those who already experience social and economic marginalisation their ability to maintain their cultural and religious identities is severely threatened. This is especially the case for those who have been internally displaced or are living as refuges in another country.

In this way, freedom of religious belief is directly linked to heritage. When this heritage is lost or endangered, the ongoing survival of minority religious communities is at risk.

As another of my interlocutors described, ‘It is so essential for the Assyrians to be in their homeland it is like when the fish leaves the water, it can’t live without it – how will the Assyrian community survive if they are not in their places?’

Sofya Shahab is a Research Officer with the Coalition for Religious Equality and Inclusive Development (CREID), an international programme led by IDS.