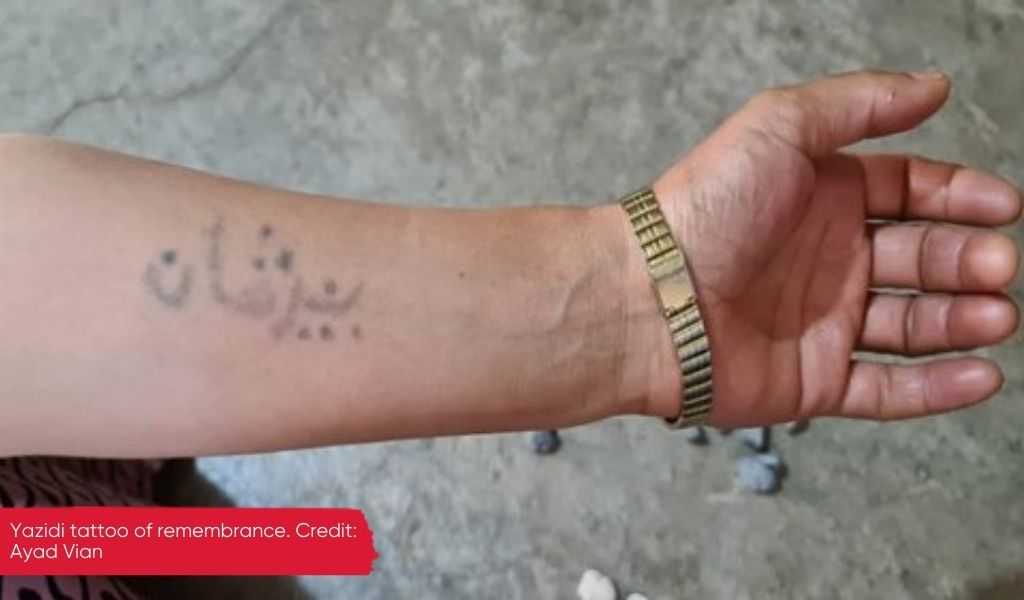

With a long history of persecution, the Yezidis recently experienced a genocide at the hands of Daesh in Iraq. As well as systematically killing and kidnapping thousands of Yezidis, Daesh also destroyed their shrines and temples, effectively trying to eradicate all trace of a people following one of the world’s oldest religions. In brave defiance, young Yezidis are reviving (and modernising) an old custom: tattooing. Sofya Shahab, from the IDS-led CREID programme, and Ayad Vian* from CREID partner the University of Duhok, write about why it’s important not to overlook intangible heritage practices to assure the survival of communities.

Yezidi tattoo of remembrance credit Ayad Vian

Throughout history the construction and destruction of heritage has been an ongoing feature in the contest to control territory and memory. This is due to the manner in which heritage provides material and emotional anchor points that enables communities and their leaders to shape identities.

Since 2014 and the rise of Daesh in Iraq and Syria, the heritage of the region has come under increasing threat. This particularly applies to minority ethno-religious groups, such as Yezidis who are now using their heritage as a means of asserting their rights and identities.

Alongside the rehabilitation of tangible heritage sites, such as the shrines and temples that had been destroyed by Daesh, Yezidis are also reclaiming their intangible rites and heritage practices. This is particularly important for those who remain displaced and living in one of the camps scattered throughout the Kurdistan region as they are unable to access the tangible sites and landscapes which had previously situated their community.

To combat the physical and existential displacements arising from the loss of their homes and heritage some Yezidi youth and women are reviving an ancient practice of tattooing among their community.

Traditionally Yezidi women would tattoo designs – most often dots – on their faces and hands. Within a philosophy grounded in nature, this was believed to be a means of relieving pain and inflammation from the area tattooed and was especially common in Sinjar and among the Hawiriya clan.

Hiyam explained that ‘Many women who have sore legs or headaches resort to local medicine after they lose hope in medicine. They put a tattoo in the form of a circular dot in the place of pain, then the patient would be cured from this pain’.

Alternatively, tattoos could be used to ward against envy (similar to charms used to guard against the evil eye). In this instance, girls would be tattooed at birth: using the mother’s breast milk and charcoal to make the dye during a celebratory ceremony involving the women in the community.

Traditional Yezidi tattoo against envy. Credit: Ayad Vian

Among Yezidi youth, tattoos are becoming popular as a means of connecting with this traditional heritage practice, proclaiming their religious identity, and asserting their presence in defiance of Daesh’s attempts to eradicate their community.

For these young people, tattooing is becoming increasingly relevant and symbolic, especially given Yezidi practices which traditionally utilised tattoos as a means of grieving for and preserving the memory of a relative who is lost or has died. It is estimated that 10,000 Yezidis were kidnapped or killed by Daesh and approximately 3,000 Yezidi women and girls who were forced into sexual slavery are still missing. As such, symbols or names are being tattooed on the body to pay tribute to those victims and survivors of Daesh.

Linked to this, tattoos are also being used to demonstrate a bond of love and attachment. Within the Yezidi tradition, two people can become linked by carrying the same mark upon their bodies. A part of them resides upon and with the other.

While Yezidi youth are using more standard methods of tattooing than their forebears by inscribing the ink on their skin with electric machines, the very act of incorporating a visual and permanent marker of their Yezidi identity on their bodies is both reviving this more traditional aspect of their heritage and defying attempts to eradicate them . By visibly showcasing their faith and community, they are demonstrating their refusal to hide despite the persecution they have faced.

Media and academic coverage of heritage destruction most often focuses on tangible sites and objects, such as that wrought by Daesh at Palmyra and the Mosul Museum. But doing this overlooks a core element of heritage which is that it is frequently intangible practices that bestow meaning and value on these spaces.

By destroying Yezidi shrines and temples Daesh attempted to erase not only the physical markers of the community but also the activities performed within them that work to cement belonging. As such, culture and people are not only erased through the destruction of the tangible manifestations of their presence and history in a place: identity can equally be lost through an inability to practice culture, including language, rituals, ceremonies, artistic performances and artisanal skills.

By reviving traditional practices, especially within IDP camps, Yezidis are reasserting their identity and maintaining core elements of their community that help to preserve their culture and group.

*Ayad Akak Vian is a Lecturer at the University of Duhok, College of Human Sciences, Department of History and writer and journalist in the administration supervising the camps for internally displaced people and refugees in Dohuk province. He can be reached on ayad.a.vian@gmail.com.