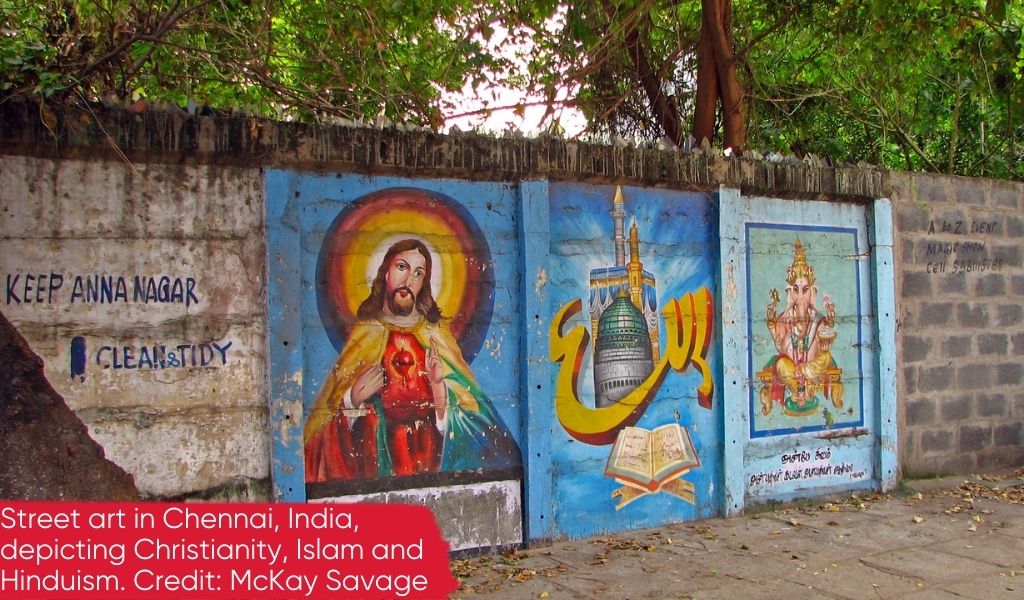

On World Day for Cultural Diversity and Dialogue, Mariz Tadros argues that the global threat we must confront is not only the protection of cultural and religious minorities, or even the minorities within minorities, but the threat to the very possibility of mixing and matching our culture, heritage and beliefs as we want to live and experience them.

The following story and those of L. and S. below are taken from a pioneering study whose authors we have had to anonymise on security grounds.

H. is a sixty-year-old Hindu Dalit who lives in one of s slums. She rents out construction equipment for her living. As a devotee of the goddess Yellamma, she goes to the temple every week. Once a year, H. and her family visit their hometown in northern Karnataka to offer a goat as a sacrifice to the goddess. H. attributes her business success to the blessing of the goddess.

L. is also a sixty-year-old woman who lives in another slum and manages three jobs to survive. She self-identifies as a Hindu but regularly prays at St. Mary’s Catholic Church and also attends the fasting and prayer meetings at the local Pentecostal church. She is deeply committed to praying to Christ and the Virgin Mary, but also continues to go to the Hindu temple once a month.

S. and her husband own a small provision store in another slum. She is a devout Muslim from Tamil Nadu. She loves to visit the dargah (gravesite) of a local pir (saint) to pray. Though she fears that the new imam at the local mosque, who was trained in Saudi Arabia, frowns upon this practice, S. and her husband will continue to pray at the dargah because that is where they can talk about their fears and ask for God’s help.

The women whose lives the authors describe face extreme encroachments from powerful political forces because they do not fit into the latter’s straitjacketed version of what Hinduism or Islam encompasses.

Homogenising ideologies around the world: India’s Hindutva (Hindu supremacists) and others

The ruling Hindu nationalist BJP party swept back into power in 2019 on the back of anti-Muslim rhetoric and Hindu supremacist nationalism. The more recent (and highly contested) citizenship law which seeks to create a confluence between being an Indian citizen and a Hindu follower is a deliberate tactic to homogenise the Indian population and created a conception of a “political community”, an “us” that is constituted around a common religious identity, Hinduism. Dalit Muslim women are amongst those experiencing the most targeting and exclusion as a result.

Powerful political forces, like the Hindutva in India or the Wahabi Islam being spread globally from Saudi Arabia, or socio-political forces such as the MaBaTha (the Association for the Protection of Race and Religion) in Myanmar, all have one thing in common: an ideological project elevating their own belief system above others. But this totalising project does not end there: these forces are also committed to obliterating all expressions, manifestations and practices within their own faiths that do not conform to their vision of the “right” dogma/doctrine/religion.

In other words, in the cases above, the Hindutva would not only seek to expel people like S. because she is a Muslim (and in the absence of an ID would struggle to meet the paperwork required for Indian citizenship), but they would expect H. and L., who are both devout and self-identifying Hindus, to think, behave and practice Hinduism in ways that are in total conformity with what the Hindutva teach about the “proper” way of worshiping.

The Hindutva would frown upon H.’s animal sacrifice, which is an ancient folk practice in some parts of India, and L.’s worshipping of a Christian deity. The imam disapproving of S. and her husband visiting shrines to say prayers, a space in which they find consolation and hold on to as part of their heritage, is also symptomatic of the same totalising, homogenising agenda of ‘purifying’ Islam of Sufism and its associated practices.

Beyond the actual targeting of cultural, ethnic, and religious minorities who do not share the same faith, what is at risk here from totalising homogenising political forces and what can we do about it?

Eclectic and syncretic faith practices essential to people’s wellbeing and resilience

The ability to engage with faith in eclectic and syncretic manners represents for many poor people a set of repertoires of strength, resistance, coping and consolation. Attempts at stripping them of their dynamic religious agency are an assault on one of the fundamental tenets of their wellbeing.

We need to challenge the legitimacy of those who proclaim a purist version of a religion by showing historically how accommodation of cultural and heritage practices has always been an expression of faith (see example of feast of Eid al Ghettas in Egypt). This would not only apply to Hinduism in India but to many faiths globally, where popular and lived experiences of spiritually have shaped and re-shaped the meanings and expressions people ascribe to their faith.

Rethinking our advocacy campaign

Could it be that the years of struggle for freedom of thought, conscience and religion inadvertently reified identities that are actually dynamic and fluid? Could it be that in addition to defending the rights of Muslim and Christian minorities in India, we also need to defend the rights of Hindu Dalits, such as H. and L., who risk being harassed because their worship does not conform to the Hindutva way?

At a time when the assault on religious and ethnic minorities around the world is so acute and pervasive for people across different faiths and geographic locations this in no way suggests that we are equating the scale and intensity of suffering say of Buddhists who do not conform to the MaBaTha version of Buddhism in Myanmar with those of Rohingya Muslims or Christians from Kachin. It is undoubtable that the protection of religious and cultural minorities and indigenous people’s right to distinctness and difference in the way they express their religious and cultural identities is pressing and urgent. However, in defending their right to distinctness, or cultural diversity, we sometimes forget that there is also a broader struggle against the political and social forces in our midst which seek to homogenise what “us” as a country, faith, or community should look like.

While being respectful and mindful of the different kinds of experiences of oppression associated with distinct intersecting identities, we need to protect against all forms of otherisation – not only from one dominant political force in relation to those who do not prescribe to the same faith, but to the very idea of limiting, containing and suffocating the possibilities of people mixing and matching their beliefs.