In this article, Dr Maha Ibrahim Jasim from the University of Mosul shares her experiences of working with young people from the Chaldean Christian minority community in Iraq documenting and preserving the oral history of their elderly, to ensure the survival of their heritage after decades of conflict.

Credit: Mazur/catholicnews.org.uk (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

My journey with preserving the heritage and culture of minorities in Iraq started in September 2020 six months after the global Covid-19 outbreak. This journey was one of its kind, bringing my attention to Iraq’s rich and diverse heritage when working with a group of young people from the Chaldean Christian community.

The history of the Chaldean community in what is now Iraq dates back to ancient Mesopotamia, which was the land of several ancient civilisations like the Akaddians, the Sumerians and the Babylonians. The fertility and subsequent prosperity of the land of Mesopotamia with its two rivers, the Tigris and Euphrates, made it the dwelling place for numerous religious and ethnic groups who have inhabited these areas and built their life there throughout the centuries.

In Iraq, there are four main Christian denominations who have inhabited this region: the Chaldeans, the Syriac (Aramaic),the Assyrian Christians and the Armenians. Chaldean Christians, who make up more than two thirds of all Christians living in Iraq, are specifically concentrated in the regions of Alqosh, Karamles, Talkeppe, Batnaya, and Basqopa in northwest Iraq.

As an indigenous minority, their history has been tumultuous with periods of both peace and persecution. Recent conflicts, including the rise of the militant group Daesh who took control of Mosul and much of the surrounding areas in 2014, led to the mass displacement of Christians from these areas. As well as Daesh’s direct attacks against Christian heritage, such mass displacement risks disconnecting these communities from their social and religious heritage that facilitates a sense of belonging and cohesion between people.

Working with young Chaldean Christians to document and preserve their heritage

As part of a collaboration between the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) and the University of Mosul [under the CREID programme], I have been working with young people from the Chaldean community. As a CREID-Iraq faculty coordinator, I worked alongside communities to recruit young people to conduct interviews with the elderly in their communities, many of whom have unique knowledge and untold stories relating to the heritage of the Chaldean Christians of Iraq. These interviews were both recording oral history (spoken life experiences) and discussing intangible heritage.

We began by recruiting young people, whom we called Heritage Gatherers, based on their age, previous experience working with communities and groups, their position at the time of recruitment and other factors including their desire to preserve the heritage of their community. Many of the Heritage Gatherers had previous experience working and supporting people, some had previously worked in documentation and archiving, while others were themselves craftspersons whose families had long worked in these industries that are directly rooted in the traditions and heritage of their community.

The heritage gathering started in March of 2021 after a 4 week extensive training course run by each of the faculty coordinators, before the young people embarked on their journey in approaching the elderly in their communities to preserve their unwritten and oral heritage.

This journey involved documenting the stories, heritage and histories of their communities through video or voice recordings combined with photos which captured the surroundings during the interviews. Topic interviews focused around a particular aspect of communities’ heritage while oral history interviews documented the life events of elderly members of the community. Mostly the processes covered in the topic interviews were video recorded to show the steps involved in it. The collected data are then saved under a unique code and a name and uploaded onto a secure digital platform hosted by IDS. This material will be archived by IDS for the the Iraqi communities whose heritage is represented and for future generations to help preserve the heritage of minorities in Iraq, including the Chaldeans.

Young people feared losing their heritage and identify as a result of conflict and displacement

For many of the Heritage Gatherers, participation in our project was motivated by recent experiences of conflict and displacement, as they feared losing this heritage and subsequently an important part of their identity altogether if it wasn’t in some way documented. Their elderly interviewees, who were between 60 and 80 years old, shared their memories and untold stories of cultural and heritage practices which are in danger of dying out.

Some of the interviews were carried out in Alqosh in the Nineveh plains which is the home of Chaldean Christians and one of the few regions to escape the Daesh invasion in 2014. It is famed for its monastery, Rabban (Saint) Hormizd, carved out of the mountain by the saint himself in 640 A.D. and in April each year, the people of Alqosh (Alqoshis ) celebrate St. Hormizd by gathering together, preparing food and climbing up the steep mountain to the monastery. They wear traditional dress whose vibrant colours and special fabric with specific details distinguishes them from other Christian groups.

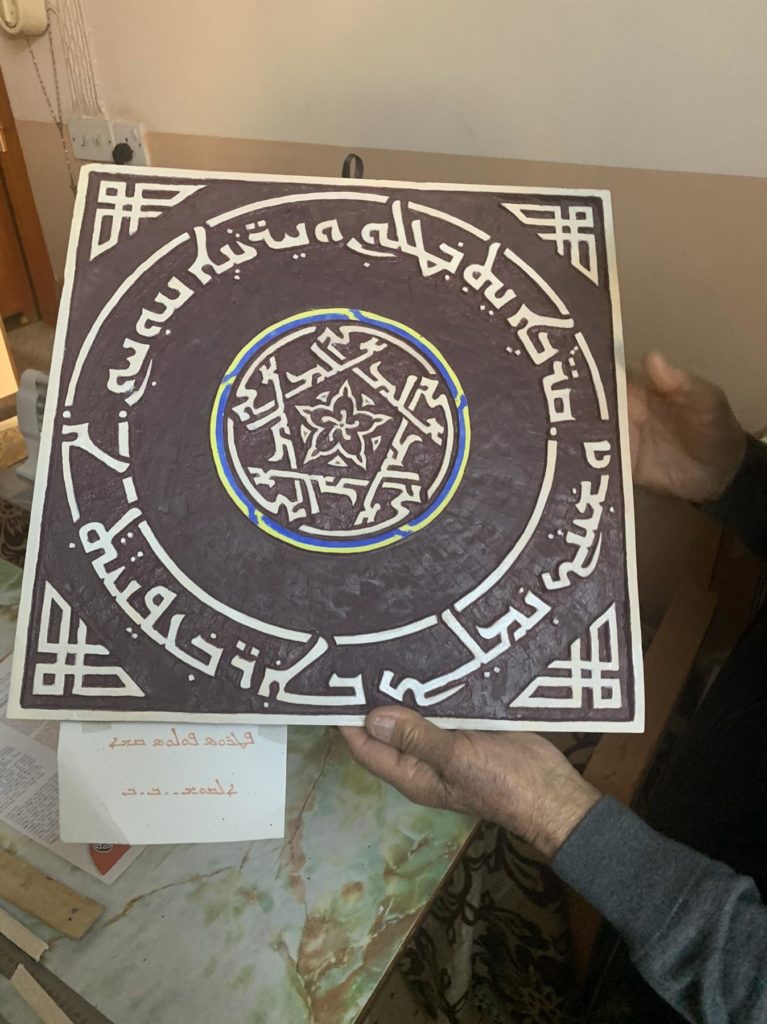

As a result of this project, I’ve learnt so much about the Chaldeans unique and vast heritage in Alqosh. For example, one heritage gatherer interviewed a very well known carpenter in Alqosh who earns his livelihood making different forms of the Christian cross used for celebrations. Another interviewed a respected calligrapher who is unique in his ability to write both Arabic and Aramaic calligraphy, and can carve his writings on both wood and paper.

The Chaldean celebration of Easter in Karamles, another city with a sizeable Chaldean community, is very particular and has been filmed by a Heritage Gatherer in a video which showed people from all age groups carrying the Palms and walking in the streets side by side.

Why this has been a learning experience for me

Embarking on the heritage gathering programme has been a life experience for me and the first time that I have chosen to join a programme focused heritage and heritage gathering.

As a linguist with a PhD in language related studies of Mesopotamia, I have worked for the last five years on documenting an Iraqi Arabic Mesopotamian dialect which involved analysing the recorded interviews of people speaking in that dialect.

This project Iraq has brought my attention to the fact that displaced communities fear not only the loss of their heritage and traditions, but also the loss of their very identity through their language which is subject to change (levelling) or even loss, if there are no efforts to preserve it. As well as the heritage traditions being shared, the elderly have, to a certain extent, preserved vocabularies and lexical terms that can also be considered as linguistic heritage. Therefore putting the effort into recording the voices of the elderly talking about their life experiences is one way to preserve the heritage of these people.

Our heritage gathering project has brought hope to communities

With all the instability in the region over a long period of time, the idea of involving the young people in preserving their heritage has brought hope to such communities that their heritage can still thrive no matter what the circumstances, if all community groups are willing to cooperate. In the words of the young people, heritage gathering has been a very special and unique life experience where they have been introduced to some aspects of their heritage they were not aware of and they have had the privilege of being the first to document the heritage of their community and ancestors directly from the tongues of the elderly in their community.

The CREID/University of Mosul project is the first step in documenting and preserving the heritage of the Chaldean community in Iraq where their second biggest fear after the displacement is that the younger generation in the community will no longer be able to keep a record of their own heritage, their own relationship with their land; the land of ancestors, the hallmark of their own identity. Therefore, this project as it works now brings with it hope to the Chaldean community which has not failed to thrive in spite of all of the difficulties.

See also…

Cultural diversity and development: heritage gathering in post-conflict Iraq

Heritage rooted in landscape – memories and cultural survival in Iraq

Covid-19 and Daesh attacks threaten the survival of Iraq’s religious minorities