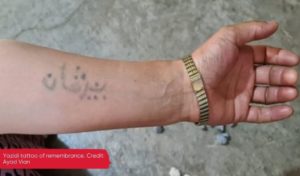

In this interview with Mari Makramalla Monir, Thoraya Saleh Salib talks about how she is proud of the tattoos, which she inked herself, and encourages the next generation to do the same, as self-expression and bodily autonomy are powerful ideals to pass down.

Men and women from religious minorities have from ancient times inked their bodies to proclaim their identity. The Copts are one of the oldest surviving Christian communities of the Middle East, and the practice of religious tattooing dates back centuries. It is a mark of defiance, pride and solidarity in the face of adversity.

Thoraya Saleh Salib is a 68-year-old housewife from a small village in Egypt. She has four tattoos altogether, including a traditional cross, as well as green tinged designs on her face and wrists which Thoraya is proud to wear.

The tattoos have particular resonance among her rural community; “they used to say, “having tattoos on hands, greenish as molokheya (an Egyptian soup made with green jute leaves)”. They mean that having these tattoos, like this one (two lines on chin) makes one looks good”.

To create the designs, Thoraya used a thorn from the leaf of a palm tree to draw blood, before adding molokheya to the wound to leave a vivid green hue as the wound healed.

Thorya remembers that her mother had similar designs on her face and hands, though the specific line patterns differed.

She would encourage the next generation to do the same, as self-expression and bodily autonomy are powerful ideals to pass down.

“If they want to make one, let them make one. It is our right to do anything we want with our bodies. No fear. It is our right to make a tattoo on our arms. The cross won’t be removed.”

Thoraya was interviewed by Mari Makramalla Monir as part of CREID’s oral heritage project in Egypt.