In this heritage case study, Nidaa Khalil Aswad interviewed and photographed, her grandmother Nemsha Shlo Smo. Nemsha was born in 1938 and has lived in Behzabi, north of Iraq, since childhood. She recalls it was a tough life because of the harshness of economic conditions and the fear that gripped Yazidi women of being assaulted, or killed, when they journeyed into the mountains.

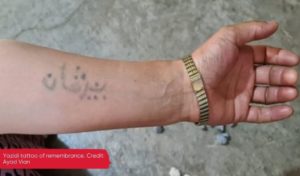

Men and women from religious minorities have from ancient times inked their bodies to proclaim their identity. The practice of religious tattooing dates back centuries. It is a mark of defiance, pride and solidarity in the face of adversity. This case study is part of a series on heritage tattoos from Egypt and Iraq.

Nemsha engaged in many income generating activities, ranging from agriculture, to clothes making, to shop maintenance. She recalled that when she was 5 years old, she – together with other family members – brought some milk from the mothers of female offspring (it must be a baby girl) and soot from the baking oven, and for one hour every day – for a period of ten consecutive days – she would prick the skin on her face and hands with a needle. The blood drawn would form a black crust, which would eventually fall to reveal a deep blue colour underneath that she says has maintained its vibrancy ever since.

Nemsha says that the three dots on her face and hand were made as a form of beautification; she has prided herself on tattooing them in exactly the same way as her mother, grandmother, and sisters did.

Nemsha is keen to highlight that while Arabs living in their region would also engrave tattoos on their legs, it is not the same as the tattoos that she and her Yazidi community engrave. Nemsha considers the tattoos that she and her community engrave a unique feature of Yazidi heritage that has been passed on intergenerationally.

Nemsha was interviewed and photographed by Nadia Noori Saloo as part of the CREID project to develop the capacity of youth to document their oral heritage under threat.